Why do some people dismiss contradictory evidence so quickly? Why do

others seem endlessly persuadable? Why might we find ourselves

trusting ChatGPT or another LLM more than our local politician or even

our financial advisor?

These are not just philosophical or psychological questions. And they all connect to a simple but powerful idea: Bayes' Theorem, which describes how to update what you believe in light of new evidence.

Let’s start with two everyday scenarios:

You’re shopping for a used car. You see a 10-year-old Toyota with

a low price tag. It looks clean, the seller seems honest, but you’ve

heard "old cars are money pits." Should you trust your gut? Pay for a

mechanic’s inspection? Walk away?You read online that a new diet dramatically lowers cholesterol.

The study is small, but it's shared by a friend who swears by it.

Should you change how you eat immediately? Wait for more evidence?

Dismiss it as hype?

These are classic problems of updating beliefs with new data. We each

have priors - our existing knowledge and assumptions - and we get new

evidence. The question is: how should we combine them to make better

decisions? This is exactly the problem Bayes’ Theorem addresses.

The Equation in Plain English

Bayes’ Theorem is usually written

Translated: Prior belief + New evidence ⟶ Revised belief. In other words, if you were already convinced of something (strong prior), you don’t change much when you see weak evidence; if you weren’t sure (weak prior), even small new evidence can sway you; and if the evidence is overwhelming, it can change even the most stubborn mind - at least in theory.

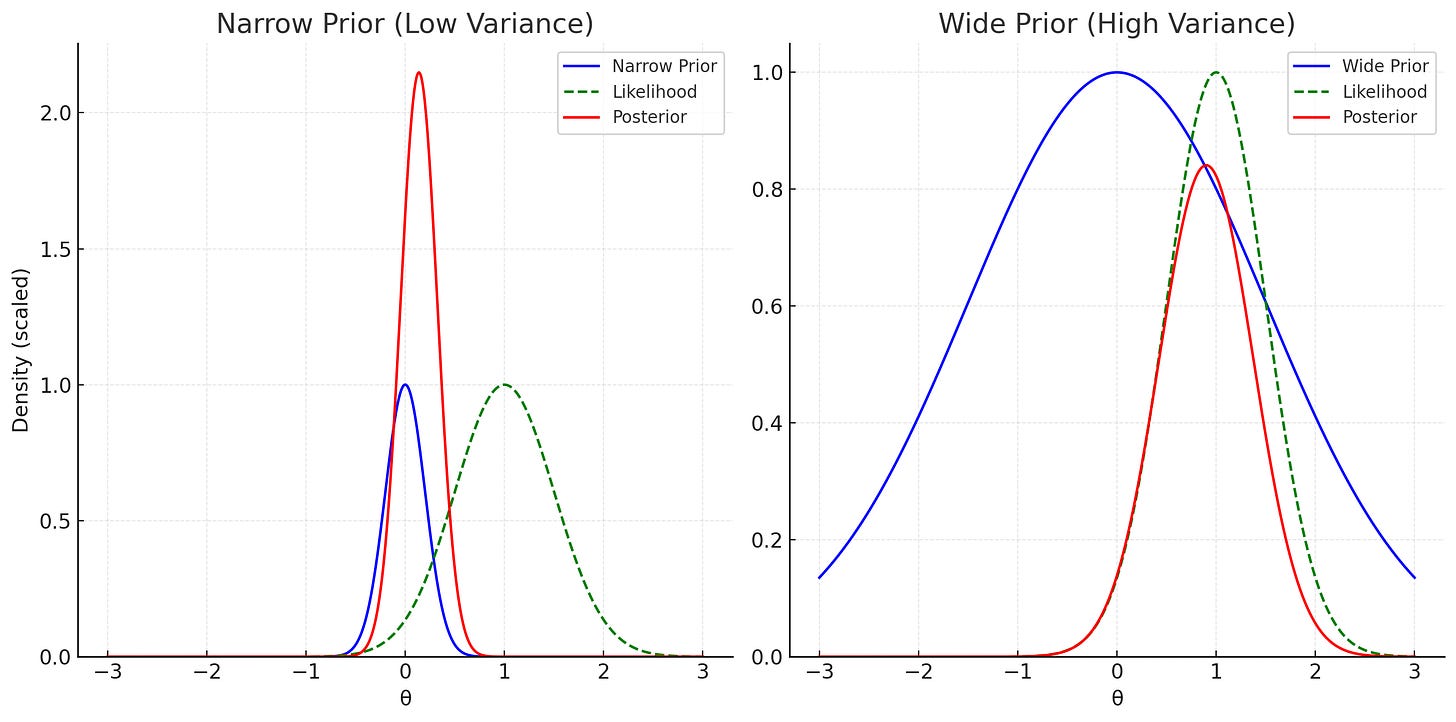

The Role of Variance and Strength of Priors

A key feature of the prior isn’t just its mean (what you expect), but also its variance (how certain you are). A narrow prior means you're highly confident. New evidence has to be very strong to shift your belief. A broad prior means you're open-minded. You let data speak.

Consider our car-buyer: If they have a strong prior that "all old cars are junk," they may ignore the clean inspection. If their prior is broad, they’ll take the inspection more seriously. In Bayesian updating, variance reflects your willingness to learn.

The LLM Advantage: Priors Built on Vast Data

Now think about how large language models (LLMs) like ChatGPT work.

They don’t just parrot text. They’re trained to model the probability distribution over words and concepts - essentially, they learn a prior over language and knowledge from a staggering volume of public data.

Their prior is built from billions of sentences, books, scientific papers, web pages, and conversations.

It’s not "all over the place" in the sense of having no bias—but it’s averaged over far more experiences than any single human could ever see.

This is a crucial advantage: LLMs can form broad but informed priors, reflecting the diversity of human knowledge. That means when you ask an LLM about, say, the reliability of a 10-year-old Toyota, it "knows" not just one person's bad experience but the distribution of opinions and data on the subject. When new information arrives (say, a clean inspection report), a well-calibrated system updates proportionally -balancing prior expectations with new evidence in a way that resembles Bayesian reasoning.

The Human Problem: Overconfident, Biased Priors

Contrast that with humans.

We often have priors formed from limited, local experience:

The mechanic who once got burned by a 10-year-old Toyota.

The dieter who read one success story on Facebook.

The executive who bases strategy on their single big win 20 years ago.

Worse, people often overstate the certainty of these priors:

"I know for sure these cars are lemons."

"Trust me, this diet works."

"This is the only strategy that can work."

When someone’s prior is too narrow given the real evidence behind it, Bayes’ Theorem predicts what happens:

They will underweight new data.

Their posterior belief remains stubbornly close to their prior.

They “block learning” because they gave their prior too much power.

Why Do People Trust LLMs More Than Financial Advisors or Politicians?

This may help explain something striking: Many people say they trust ChatGPT more than their financial advisor, politician, or even corporate executive.

LLMs aren’t "smarter" than the best human experts. They don’t “reason” in the human sense. But:

Their training forces them to reflect the broadest possible prior over human knowledge.

They’re less likely to dismiss contradictory evidence because they aren’t anchored to personal, local, emotional experience.

They “listen” to more voices, more contexts, more outcomes.

They are not free of bias - far from it. But their bias is often more representative of the aggregate human experience than any single person’s limited, overconfident view.

A Final Thought

Bayes’ Theorem is not just a formula; it is a philosophy of humility. It reminds us that every belief is provisional, weighted by what we know and how much certainty we claim. LLMs succeed not because they are smarter than the best of us, but because they model uncertainty at a scale no individual can match.

That, in the end, is the key to how both humans and machines should see the world: be curious, be data‑hungry, and, above all, be willing to update.